By Randy Williams In "Driven," director Renny Harlin's

film about the world of open-wheel car racing, the stars include Sylvester Stallone (who

also wrote the screenplay), Gina Gershon, Estella Warren, Til Schweiger, Kip Pardue and

Burt Reynolds. But the marquee names take a back seat to the scene stealer already on view

in the movie's trailer -- the technology and ingenuity that created the spectacular

"Memo crash."

The crash sequence -- less than two minutes on screen -- is the technical centerpiece

of a film that, says Harlin, was designed to raise the bar once more for the constantly

evolving world of feature effects. "My goal was to do for car movies what 'The

Matrix' did for action movies, " the Finnish filmmaker says. "I wanted to

explore and define new ways of shooting and more than anything ... how to put the audience

in the driver's seat."

Harlin says he realized early on his temperamental star would demand teamwork, weeks of

planning and the specialized services of computer artists and technicians. Indeed, the

specific look the director wanted to achieve ruled out a number of traditional methods of

staging the crash.

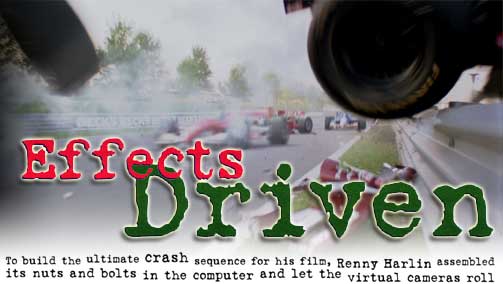

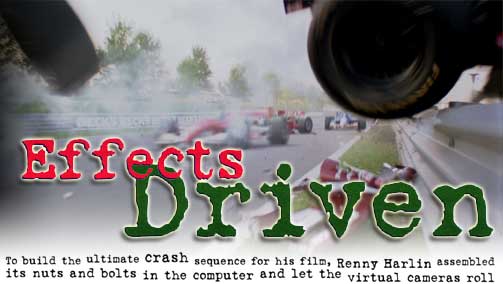

Artists at visual effects house Pixel Magic produced

entirely computer generated visual effects shots for DRIVEN, including this shot from the

climactic 'Memo's Crash' sequence. Click on the image for a larger view. |

Stunt drivers could not be employed because open-cockpit race cars afford them no real

protection in a crash. Radio-controlled vehicles were equally problematic. Although a

remote-control system was devised to crash cars traveling more than 100 mph, the signal

could be interrupted by a kid with a walkie-talkie who happened to be in the area using

the same wavelength.

It was Harlin's effects coordinator Brian Jennings who came up with a viable solution.

He fashioned a complex pulley system that could tow a car rigged with explosives and

breakaway parts at a very high speed to a designated mark, where it could be detonated.

Nearly two dozen of the crash cars were constructed, but the real trick was to get the

fabricated vehicles to break up precisely as a real one would. "Renny worked it out

with a physicist," Stallone says, "that if a car was stalled on the track and

another one hit it at 200 mph, the end result would be that it would fly eight stories in

the air and travel nearly 400 feet. It would have that kind of reaction."

Shot on a test track in Montreal using as many as 16 cameras, Harlin captured the Memo

crash (named after a character in the film) from every conceivable angle. The director

used Rollvision -- a remote-controlled camera head that can tilt 180 degrees as well as

roll and pan 360 degrees -- along with a very small camera called the Eyemo, which was

rigged to a car's suspension for a fast-moving perspective.

"In terms of the shooting and editing style, Renny wanted a very real and raw feel

using lots of cameras and (he was) not particular about perfect focus," Jennings

says. "It is in some ways like a documentary, real-life feel so that you're in the

car and things are shaking and not perfect."

Only two of the ten racecars featured in this shot actually

exist in real life. All other elements of the shot (eight racecars, shadows, tire and

engine smoke) is computer generated. Click on the photo for a larger image. |

In addition to the various camera cranes, which moved above, around and among the

racing cars, Harlin also employed a FotoSonics camera, which shot more than 300 frames per

second to capture the fiery explosions. He even used cameras in steel casings so that the

cars could actually crash into them to give the effect of debris flying right into the

audience. (To create the slow-motion visuals for the crash scenes, "Driven" used

an Arriflex 435 motion picture camera, whereas "The Matrix" relied on a series

of still cameras to achieve it "hang time" effect.)

In filming this sequence, only one car could crash on the wires -- it wasn't safe to

have other vehicles driving near the rigging. So, Harlin shot it knowing he could add

computer-generated (CG) race cars later in post-production.

Ray McIntyre Jr., a visual effects supervisor at digital effects house Pixel Magic, was

commissioned to create those CG cars, as well as generate virtual rain and fan-crowded

grandstands for other racing sequences. Using Pentium-based computers with Windows 2000

operating systems and Lightwave 3D software, along with Apple Macintosh G4s running Adobe After Effects and Pinnacle Systems' Commotion, the crew at Pixel Magic began the complex

technical process of digitally building the Memo crash.

Portions of the effects work were based on a computer model of one of the leading race

cars, a Reynard, which had been furnished by Jennings. "Reynard supplied us with a

diagram and a parts list, so we built a computer car with all the same parts as the real

ones," Jennings says. "Body surfaces, bolts, aerodynamics, even signage -- our

computer car had all the same dynamics as the real ones, so when we simulated the crashes

all the pieces would be there to analyze."

(from left to right) Pixel Magic visual effects supervisor

Raymond McIntyre, Jr., 3D supervisor Micheal Hardison, compositing supervisor Todd Vaziri,

visual effects producer George Macri. Click on the photo for a larger image. |

The first phase took about 10 days and primarily involved animatics or

previsualization, which McIntyre describes as storyboarding in the computer.

"Renny wanted something no one had ever seen before, no race fan, no

moviegoer," he says. "In describing his goal, Renny said he wanted an

'out-of-body' experience for the fans of what the driver was seeing. That meant the driver

in a crash reacting to the crash and everything in his immediate surroundings (fire,

debris) is in slow motion, but the world is in real time. The other race cars are whizzing

by almost hitting him in real speed, yet the rain and flying debris are in slow motion.

"Because the filmed crash didn't have the climactic effect they'd hoped for,"

McIntyre adds, "we took the first 2-3 cuts of the real crash and merged it with the

remaining dozen cuts in computer animation. To do that seamlessly was a very, very

complicated process."

In order to re-create the exact details from the filmed sequence, Pixel Magic basically

"created geometry in the computer," he says. "Like an architect would in

his renderings, we created in the computer a three-dimensional wire frame of the track

surface, the guardrail, the billboards and off in the distance the sky and trees."

The effects designers were then able to map an image onto the geometry that allowed

them to "move" the camera to change the mood of the shot or alter a given

perspective. "We made virtual camera moves out of video plates that didn't have

camera moves in them to begin with," McIntyre explains.

Bridging real footage with computer-generated images in an almost continuous fashion

was made possible by Pixel Magic's compositing supervisor, Todd Vaziri, who came up with a

transition method called a 'Slingshot,' McIntyre says. "What that slingshot

does," he says, "is take the audience into the driver's out-of-body experience.

The driver (crashes into) the guardrail as we go from the real car crash to the CG crash.

The scene begins to kind of vibrate like a high frequency and zooms in via tiny

increments. Then, all of a sudden (the point of view) rushes into the helmet of the driver

and pulls back in a reverse method of that high-frequency shake and zoom technique into

the first total computer-generated shot.

Four computer generated cars, tire smoke and engine smoke

were added to this intense scene, where a racecar actually hits the camera sending it

flying. Click on the photo for a larger image. |

"That's an indication that we rushed into the driver and pulled out and you, the

audience, are now feeling what the driver feels and sees as he experiences it,"

McIntyre continues. "As opposed to a race fan who sees everything go by in real time

and barely has time to react to it, you are now experiencing what the driver is, which to

him is trying to save his life. He's doing everything in his power to deal with (the

crash), so therefore it's not happening as fast to him as it does the person watching it.

That is what the first transition from the real crash to the first CG shot shows you. From

that point on, everything is computer generated."

With his team of Vaziri, CG 3D supervisor Micheal Hardison and visual effects producer

George Macri, McIntyre presented the finished sequence to Harlin and Jennings. Afterward,

the Pixel Magic crew made some adjustments based on their comments, and the director and

Jennings met with the film's editor, Stuart Levy, to edit the previsualization piece into

the sequence.

Although the Memo crash might get less than one percent of the film's screen time,

those few moments reflect the attraction of virtual technology for an action-oriented

filmmaker and the advances made since the release of earlier racing movies -- such as

"Grand Prix," "LeMans" and "Days of Thunder" -- all of which

were considered technically adept for their time.

"This film could be done completely practically with no visual effects,"

Harlin says, " but our ability to digitally modify the action and cars enhances the

live racing footage, allowing us to move the camera seamlessly and show you new things in

new ways. With 'Driven' you are dealing with absolute reality and people know what things

look like. So no matter how good the technology is, with reality-based films especially,

you have to conduct your shots so that they are believable and not an unreal exercise

removed from accurate storytelling."

Pixel Magic's web page: http://www.pixelmagicfx.com

DRIVEN Home Page: http://www.what-drives-you.com

DRIVEN (c) 2001 Warner Bros. and Franchise Pictures

The Hollywood Reporter: http://www.hollywoodreporter.com